A Conversation on Multiplicity, Illustrated Clickbooks, and Western Media Tropes with Dav Yendler

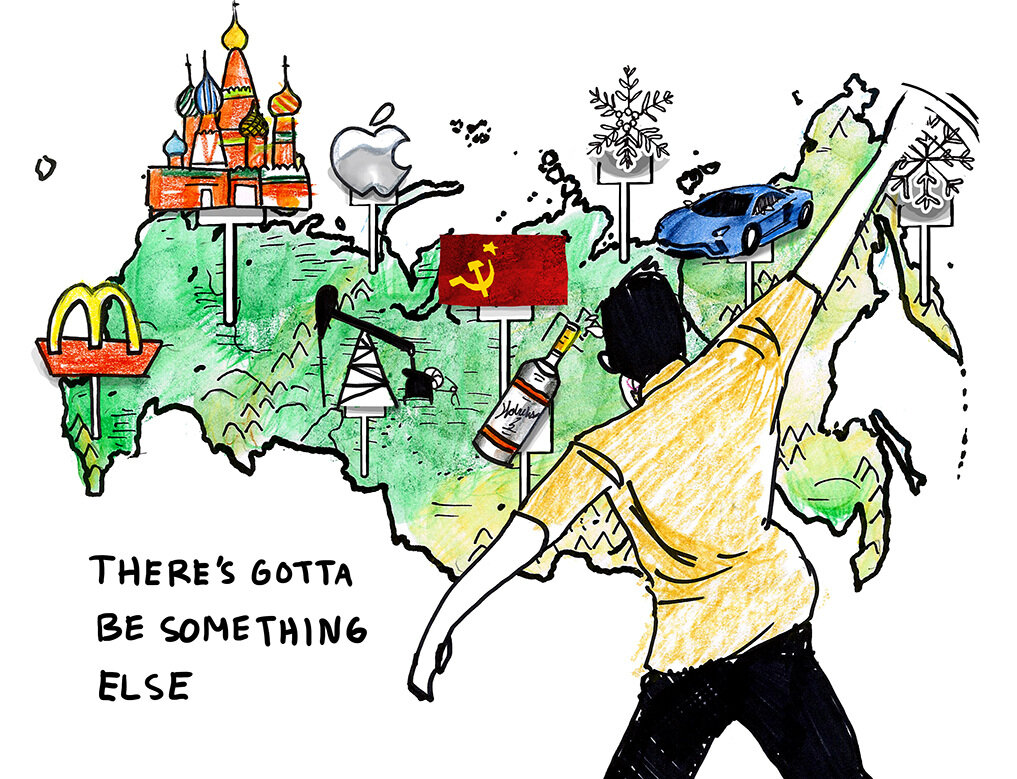

Americans have a lot of ideas about not only themselves, but the rest of the world, too. Specifically, Americans have a lot of ideas about Russians. Call it the modern iteration of the Cold War legacy, or call it the direct aftermath of 2016, but Russia and Russianness have been portrayed in the West as very particular concepts with a very particular set of attributes. Of course, there is no one answer to what constitutes Russia and Russianness, and it is this very notion that is explored by illustrator and designer Dav Yendler in his recent clickbook, “Other Russia.”

I was lucky enough to explore these pressing issues through an in-depth conversation with Dav, an L.A.-based illustrator with Russian immigrant parents. Throughout our discussion, he dove into the process of creating his clickbook, including utilizing his artistic network to obtain interview subjects, and the questions of identity and portrayal that informed his phenomenally crafted, inquisitive work. As someone who just completed a graduate thesis concerning Soviet history and especially identity formation in the Soviet and post-Soviet era, “Other Russia” piqued my interest not only artistically and journalistically, but also academically.

We also conversed on history, politics, the diasporan experience, and Dav’s other impressive projects. Read on to learn about this incredibly fascinating work and its implications for future conceptualizations regarding Russian portrayal in Western media and more!

Courtesy of Dav Yendler

As the child of Russian immigrants, what brought you to conceptualize this project as “Other Russia” and what was the process of coming to terms with your own identity and heritage in crafting this work?

Honestly, the only thing that really inspired this was the fact that in Western media, we really only see one kind of portrayal, or narrative, of Russians: as corrupt, alcoholic, meddling oligarchs. As a Russian myself, a Russian-American person, I know that that Russian exists, for sure, but that there are also other Russians. So, the whole point of the piece is to simply introduce my friends and audience to Russians that they would never find or meet otherwise.

So, in a way, this was very much inspired by post-2016, but also nods toward a longer-lasting Cold War legacy regarding the political climate of the U.S.?

Absolutely, for sure. We do a really good job of out-narrativizing our “enemies.” We don’t even have enemies anymore, really, but we only hear one kind of story about Iranian citizens, about North Korean citizens, about Russian citizens, and this project I see as a corrective to that kind of storytelling. Especially because, in the context of Russia specifically, it’s just the perpetuation of an old fight between our two countries that personally I am too young to remember. It’s our dads’ problems, not our problems, and Russian dads and American dads are having the same problems that their dads had — I don’t want to have those problems anymore. I think all the competition between us [Russia and the United States] is this last gasp of an old era. Everything I’m saying is super optimistic, of course, there’s no guarantee that peace and love and communication will win this almost century of an old fight, but I’d like it to.

Courtesy of Dav Yendler

Very well said. Your use of clickbooks as a medium allows you to employ this narrative and brings motion to your illustrations. Can you talk more about why you chose that medium and how it mobilizes the message of “Other Russia?”

I came to illustration sideways. I started off with my training as a theater director, working in performance and live events. I was working in Chicago with this salon-type event, sort of in the Bohemian sense of salon — a weekly gathering of artists coming together to show their work off, and a lot of the work shown was performative. Music or dance, poetry or monologuing, and so forth. I really wanted a way to show off my illustrations in a performative space. They first started off as slideshows with me narrating over on a microphone with live musicians in the background and the illustrations on a digital projector, and we would all work together to create this sort of illustrated spoken piece. Then, I started thinking about how I could get that experience out to a wider audience, and right around this time websites started to get really flexible and I found programmers willing to work with me.

Honestly, the first iteration of a clickbook started on Facebook, as a Facebook photo album. It was actually really nice because you load up all the images in sequence in a Facebook photo album, and it becomes shareable, and you can just post a link to the album anywhere and it will go and that’s how it started. I actually do a lot with dance and movement, and what I really like about the Facebook photo album is that it loops. So if you just tapped right forever, the animation would just keep going. So then, that naturally migrated to Instagram stories, which made for a great home for these clickbooks now, and then my website, where I worked with software developer Jack Jennings to find a code that hosted clickbooks and made the process really easy. That’s all to say, the interactivity comes from performance. You sitting there, and having your own experience, being able to stop on a frame, go backwards, go forwards, it’s part of this theatricality that’s really important to me. Making sure that you, the viewer, stay invested, because I’m not in a room with you.

Courtesy of Dav Yendler

Right, and I know that when you have performed it, someone can see it as a live performance, while another can watch it as a clickbook in their own time and space — nodding towards the versatility of that medium and presentation of your work.

Yes, that’s exactly the goal behind it.

I also felt that there was a journalistic aspect to “Other Russia," because you set out to interview subjects and portray their unique negotiations of their Russian identity. What did that process of interviewing look like? Did you face any issues of accessibility? I’m asking the latter due to my experience of conducting interviews for my Master’s Thesis on immigration into the Soviet Union after World War II and being perceived as an “outsider” due to being an American or a diasporan.

The part and parcel, or the mission statement, of “Other Russia” was to introduce American audiences to real-life Russians, which has an innate journalism to it because we need to find these people, get their stories down, and present them in ways that are palatable to Western eyes and ears. It was sort of multi-faceted; the first prong was just blasting on Instagram and Facebook to find anybody that was interested in talking to me. Instrumental in this endeavor was a friend of mine who was a theater director. She went to Moscow a couple of years ago, so I reached out to her and she put me in touch with her handler there. The handler is really hooked in with the performance and theater community in Moscow, and he connected me to a lot of his friends and a lot of friends of friends, so it became kind of like a web. I asked those people to reach out to their friends, to communicate as much as they can, because I was seeking people to communicate with me from all walks of life, all persuasions, genders, races, financial backgrounds, etc.

The next time I do something like this — and hopefully I get to continue my work, because most of my interview subjects were based in Moscow (I had a couple in St. Petersburg, and there was one in Novosibirsk, which is in Siberia) — I’d like to expand geographically and into other communities. There were eleven interview subjects, and although six of them made it into the piece itself, with all eleven being featured on my website.

Courtesy of Dav Yendler

So you didn’t go to Russia specifically for this project, it was all done via networks and digital contacts, correct?

Yes, that’s absolutely right. I actually ended up going to Russia after the project was published. I also didn’t want to publish before going because I didn’t want to get into any kind of trouble with Russian authorities, embassies, visas, or anything. I actually did meet one of my interview subjects in St. Petersburg, which was so fabulous. The painter, Roman, who is an incredibly interesting guy. He’s a classically-trained painter and a micro-photographer, he really enjoys taking photographs of insects. We were talking about his love of insect photography and how it fits into his role as an artist in Russian society, what he wants for Russian culture — really fascinating stuff.

Very fascinating. I noticed that a lot of your interview subjects were more artistically-minded, or creative, and I suppose that’s a reflection of using your network in terms of accessibility to these individuals.

Yes, that’s right. I think every single person I spoke with was interested in getting their stories out. I think Russians are very sensitive to the misportrayal of Russians in Western media, because it is very far-reaching, and they know what’s said about them. A lot of them are like, “Come visit us! We’re not that different!” Everyone was very interested to speak to me.

““I think Russians are very sensitive to the misportrayal of Russians in Western media, because it is very far-reaching, and they know what’s said about them. A lot of them are like, ‘Come visit us! We’re not that different!’” ”

That’s a great experience as an interviewer. I’m also curious as to whether you yourself feel this sense of multiplicity and if that informed this project beyond the current social and political climate? If so, how do you conceptualize your own multiplicity, and is that reflected in seeing Russia not just as a monolith, but as something encapsulating all these different realities simultaneously?

To give some more background, my stepmom is Ukrainian and my dad is Russian, and my mom and stepdad are both Americans, which helps our conversation about multiplicity. But it’s so funny — to most of my friends, I’m the “Russian guy.” I speak Russian, I talk a lot about my Russian rocket scientist father named Boris, I have a mustache, I represent that side. Do I feel Russian? Yeah, I mean, if you talk to any immigrant kid about this, you’re going to get the same kind of confusion and ambiguity. How do you feel? Do you feel Armenian, do you feel American?

Courtesy of Dav Yendler

I mean, there’s a wonderful quote by anthropologist Patricia Zavella who studies Mexican migrants, and the name of her work is called I’m Neither Here Nor There. I think that is it — it’s something that a child of immigrants feels, diasporans like us, but I also think that it extends beyond. In the U.S., where everyone wants to categorize and typify, and what I think your work speaks on immensely, we perceive it as there are Russians and there are Americans and that’s that! Or your left-wing or right-wing, and that’s that! Basically, binaries for modalities of existence that have resulted in covert or overt racism, discrimination, and an inability to empathize – and now we’re seeing the long overdue backlash for this in recent times with BLM. So the concept of belonging neither here nor there is fascinating in that it better captures the nuance of identity, not just for diasporans or the children of immigrants, but for everyone. I know “Other Russia” is not just about your identity, but also gives voice to these other Russian identities, in addition to deconstructing these rigid confines of identity, correct?

Definitely. We have, over the entire course of the twentieth century, a particular kind of profile of “Russianness” here in the States, and I think I’m uniquely suited as a Russian-American to explore the very implications of this monolithic profile. Funny enough, I was just reading how it’s a very American trait to hyphenate an ethnicity with the title of “American” to classify yourself, and no other country really does that. You’re Swedish, you’re Chinese, you’re Finnish, you’re not African-Finnish or African-Chinese. But, there’s African-Americanism, Russian-Americanism, Japanese-Americanism, etc. which I think speaks to something about us and how Americans perceive themselves. It’s like, we’re obviously a melting pot and a country of immigrants because we have this hyphenate in our diasporic communities. There’s this need to highlight disparity in order to create equity. If you’re going to level the playing field, you have to take a full survey of the playing field – feel all the dips and nooks and crannies. Part of that is labeling things as they are, which in our case, is racist, corrupt, and patriarchal. Possibly the work that we’re doing in labeling our inequities comes from the American suffix.

So maybe as Americans, we survey our playing field more and thus confront our issues more?

Yes – right now, our playing field is a mess. It hurts a lot of people, it only supports a very few, and we have to really look at that and label it for what it is – which is racist. Part of that is identifying who are the victims of racism, and who are the perpetrators. In the U.S., systemic and institutional racism is perpetuated mostly by white people, but racism ends up directly or inadvertently affecting everybody. It hurts the oppressed, but the oppressor is also hurt by the oppression. A classic example of that is how men are also victims of the patriarchy, not just women.

““There’s this need to highlight disparity in order to create equity. If you’re going to level the playing field, you have to take a full survey of the playing field – feel all the dips and nooks and crannies. Part of that is labeling things as they are, which in our case, is racist, corrupt, and patriarchal.””

Right, very true. And do you think that the hyphenated identity ends up doing more harm, or does it serve a purpose, based on what you’ve seen with how people are so quick to categorize and typify you?

That’s a good question. When I was in Russia, I went on a Tinder date — it was a kind of tourism I wanted to do. I wanted to see what romance was like out there, so I met this woman, an architect who was very fashionable and had an Instagram following with a really beautiful apartment. A sort of young woman who to me felt like she belonged in my cultural sect here in Los Angeles — liberal-leaning, into the zeitgeist, social media, the works. I was sitting there and thinking, “Oh, you’re me! You’re in my crew back in the States. You’re part of the crew that I made this piece for.” Because that’s who I made it for — I made it for my friend group, the people that I communicate and commune with, in an effort to talk about Russia in a way that they hadn’t heard before.

So we’re sitting there, and she’s talking about how much she loves Putin. This also happened when I was interviewing Dmitry for “Other Russia." He’s a theater director, he talks about his responsibility as an artist to communicate with his audience. He has what we in the States would identify as all these leftist, liberal ideals, and he loves Putin! There’s definitely something innately Russian in both of their loves for Putin, which is this fealty to strength. There’s this unifying value that Russians have, that I don’t think we have, as Americans. We all love freedom, but if you asked two different Americans what freedom meant, you’d probably get two different answers, whereas in Russia, if it’s strength, you get one answer. I think somewhere in there is an answer about the hyphenate identity in American culture, but I’m not quite sure what it is. Does anything spark for you?

I mean, to bring a bit of my academic background into the conversation, I definitely have read a lot about the paternal tradition so predominant in Russian history, before with the tsars, and then with the Soviet leaders, and now with Putin. It’s very much this ceremonial relationship to this omnipotent father figure.

Yes, which is insane, considering all of the regime changes. If we just take the last 100 years of Russian history, how many regime changes have they had? And yet, in my sense, after conducting these interviews and as the child of Russian immigrants, there is a unifying value system. Compare that to our history, which is one regime over the course of 250 years, there is no unified value system, and I think that is fascinating.

Courtesy of Dav Yendler

And to really drive this point home, Putin recently won voters’ approval to stay in power until 2036. Of course, voter fraud is not out of the question, but there seems to be a more malleable path to this type of longstanding dictatorial power in Russia, right?

Yes, especially because Russia is kind of in a constructivist mode. They’re still rebuilding from the collapse of the Soviet Union and are rebuilding their own identity, but the identity that’s being formed evades American analysis and processing, I think. I was reading about the protests in Khabarovsk, where the governor, who belongs to a political party underneath Putin’s political party, was arrested by the Kremlin and shipped away to be prosecuted for the alleged murder of four men in the 2000s. The people of Khabarovsk are partaking in an illegal protest in one of the largest protests in the history of that region – the numbers are 10 to 35 thousand people in the streets demanding for the return of their governor. By nature, these are anti-Putin protests, and in my American eyes, this is great! Amazing, people are storming the streets, police are handing out masks, no one’s being arrested, and there are tens of thousands of people protesting Putin’s actions. But then, you dig a little deeper and you find out this governor’s political party wants a return to Russian imperialism, it has these hard-core, right-wing, nationalist values, it views the Western empire and the expansion of Europe as the largest threats to the Russian state. These things, that we, in our liberal spheres, wish weren’t the case, or weren’t true of, for people protesting Putin.

““There’s this unifying value that Russians have, that I don’t think we have, as Americans. We all love freedom, but if you asked two different Americans what freedom meant, you’d probably get two different answers, whereas in Russia, if it’s strength, you get one answer.””

That’s very interesting – on one hand, we’re glad that they’re protesting Putin, but on the other hand, it seems that they’re still adhering to that unifying value system that is very much engrained on a deeper level in Russian society and history. It could also be possible, perhaps, that that kind of protesting is more tolerated than other types of protest.

Right, as opposed to protests on individual freedoms or sexual harassment.

Yes, maybe in the way that Charlottesville protestors are called “very fine people” but Antifa is designated a terrorist organization.

I agree. For me, these protests in Khabarovsk show me that no matter the ideologies between our two countries, what’s happening in Russia does not easily break up into understandable chunks. It’s not meant for our news cycle to digest easily. When I identify the anti-Putin protesters with “problematic, imperialist values,” I’m not trying to say that every person in the street is a right-winger who wants to expand Russia’s borders. I’m saying that the man that they are supporting is problematic in his own way rather than being this paragon of leftist liberalism, and that stubborn defiance of a consumable narrative keeps Russia confusing to Western media.

I think that also speaks to how one may assume that the tsarist period was very different from the Soviet period which was very different from the post-Soviet period, but that continuity really shines through. I was really fascinated by how in Western scholarship, people are really quick to typify it as the old regime versus communism (God forbid!), but when you look at it, there’s a nuance and a continuity that might not be too obvious. It’s exactly what you’re talking about, that throughout all the regime changes, there’s that unifying factor. And sometimes, Western scholars will talk about that in a negative sense (authoritarianism, paternalism, etc.), but the way you’re portraying it actually sheds light on it in a more positive sense to me, which is really interesting.

For sure. I mean, I have this big claim in the piece that there is a darkness in Russians. And the unsaid claim is that there is a lightness in Americans. I think both of our countries can use the other’s sauce a little bit. The American dedication to lightness is blinding, just like the Russian dedication to darkness. And to quickly note on the regime changes, there’s a quote that my father always drops by the author Mikhail Lermontov, that essentially Russia is a country of masters and serfs. And my dad can’t stand Russia, he hates going back and doesn’t like associating with it — which goes back to our conversation about multiplicity. It would be interesting to have the multiplicity conversation with Boris, because he immigrated. I speak two languages as well, but he speaks two languages because he was born in the other language. Anyways, so according to Lermontov, according to my father, Russia is a country of masters and serfs — this unifying value system, the performance of a patrician, all of these things. We have no such analogue in the states; in its place we’ve created this positivity, can-do, liberal ingenuity, capitalism, democracy, with all kinds of lightness which I think can be just as blinding as the Russian dourness, reliance on the patrician system, irony, all of those things.

Courtesy of Dav Yendler

Wow, I think there’s a really profound observation here. You can write a book about this, because the people that write about Russianness or Russian history and society, particularly in Western scholarship, write about it in ways that I think sometimes misses the mark, and your approach hits at something that a scholar would perhaps never arrive at, no matter how much archives they dig up, you know?

Maybe we should write a book together.

We should! There can be so much that can be done with this, and the issue with how Russianness is portrayed in the Western media is definitely ongoing, and it’s not going to disappear any time soon. It’s very valuable. I also wanted to ask you to elaborate a bit on the blinding American “lightness.” How would you say the recent happenings with BLM, political divisions over the pandemic, and generally the backlash against our government and dear leader have altered, or influenced, the way you conceptualize this blinding light?

I think that the blinding American lightness is slowly being dimmed in this moment as we are acknowledging our fuck-ups, whereas before, the American positivity, the “democratic values for all,” “freedom for all” kept us in the dark. It made issues ignorable, like systemic racism, patriarchy, violence, the state of our schools, prison, police, the whole thing. We could ignore those things under the blinding banner of lightness. But now, with Covid-19, 2020, George Flloyd, Breonna Taylor, Trump, the “light” is being dimmed in a good way. It’s less blinding, and it’s letting our eyes adjust and admit to ourselves our own reality. Perhaps this pushes us more towards a Russian darkness, which isn’t necessarily bad, but admits that there is strength in shittiness, and that you can build yourself up out of a difficult situation. Like, the garbage of bureaucracy, winter, Stalin, Khruschev – all of that can build character in a way that nothing else can. The survival of those things creates community in a way that nothing else can.

Perhaps, now, as Americans, we’re entering a little bit into that Russian darkness, in that we’re admitting our faults to ourselves.

Courtesy of Dav Yendler

That’s surprisingly a more optimistic, or more hopeful, perspective of everything that’s going on. Perhaps viewing everything as necessary growing pains we have to go through in order to better ourselves as a nation and resolve realities that were previously hidden from the general population.

I think so – if anything, Russians can be a very pragmatic people, so can see the utility in everything. In darkness, you have to make light. I hope, of course, that our current moment is contributing to a better future and a better, or more honest, balance of lightness and darkness. More truth. If we can learn a little bit from our Slavic friends about confronting truth and learning from truth to build a better future, then more power to us.

Agreed! So, something I picked up on when I was going through your interviews was a post-Soviet nostalgia for the old communist regime that some of your subjects spoke about. Did you pick up on that, and did that influence how you proceeded to portray different Russias in your work?

Can you tell me what some of those pickups were, for you?

Courtesy of Dav Yendler

One thing that stood out to me in one of the interviews was the notion that the Soviet Union had a “mission,” and now Russia doesn’t have a mission or a statement anymore and it’s just “defeat America.” Or there was another interviewee who noted how Putin brought back art for the elderly from the Soviet era, and they seemed to reminisce about the communal aspect of the previous regime.

Yes, you’re speaking about the interview with Roman the painter. He’s fascinating, his whole entomology thing comes into play here because he was creating parallels between ant society and Soviet society. Every ant has a purpose, and the Soviets were very good at giving every citizen a purpose. We can also compare that to the interview of Dmitry the filmmaker, who likes to travel the periphery of Russian rural areas to see how post-Soviet life is treating those people. He talks about how in rural areas, there’s the absence of purpose, or rather that the collapse of the Soviet Union left behind an absence of purpose that slowly is being filled with small cultural growth, agrarian efforts, farmers going back to nature, the whole thing. I can really just spend a whole universe inside that interview, because it’s so fascinating.

To speak more on that absence, I was born in 1985, and if I were me, born in Russia, I would’ve been five or six years old when the Soviet Union collapsed. It is my generation that is the most fucked, according to this guy Dmitry. So this population is recalcitrant, angry, vindictive, and spiteful that they have no place in the history of Russia, as they’re from the transition period. It’s really interesting, because that’s me! But because I was born here, I have a different experience. So in terms of post-Soviet nostalgia, Roman the painter said it best: it used to be that the Soviet Union gave everyone a purpose, and now, what’s the purpose of Russia? To defeat America? That’s not a purpose, so what’s left? He left it as a question, and maybe the answer is in these rural areas on the periphery, where Dmitry is exploring. The small communities are creating their own self-identity, not around the government or Sovietness, but themselves — perhaps in a more “American” way, if you will, and that’s where the future is. Who’s to say?

““What’s happening in Russia does not easily break up into understandable chunks. It’s not meant for our news cycle to digest easily ... that stubborn defiance of a consumable narrative keeps Russia confusing to Western media.” ”

Incredible insight, and the whole notion of periphery versus the center, particularly in regards to Russia, is huge historically and presently as well. My thesis focused on that tension between where identity comes from, and I went at it with a specific angle (due to language and accessibility) through the lens of Armenian migrants who “repatriated” to the Soviet Union in the 1940s. This issue of periphery versus center, which I framed as a Soviet issue, is clearly still relevant in the post-Soviet period, perhaps even more so for the identity formation Dmitry is exploring. Because Russia is so big and has all these different ethnic groups and peoples under its reach, there’s this tension between the Russian Orthodox, Slavic center and the indigenous Siberians, the Yakut and the Arctic peoples, Central Asians, and South Caucasians. That unique issue of center versus periphery is perhaps indicative of Russia’s strength, but the monolithic portrayals we get in Western media completely wipe out this multiplicity and nuance. You hitting on that, and saying that’s where the strength in Russia is and that’s where purpose will be found, that is potentially the answer. I would presume that no other empire, or multiethnic entity, has ever really operated as much in the same way of center and periphery as Russia has for the past several centuries, at the very least.

I agree, I think we’re in a very interesting moment, and we should keep our eyes peeled for what happens. Especially because our view of Russia is very Moscow-focused, which I don’t think is true for them, in terms of us. Like, they’re not Washington D.C.-focused, Los Angeles is just as much America as Dallas is for Russians, whereas for Americans, it’s just Moscow. I think that is felt within Russians — the filmmaker Dmitry talks about how Moscow self-propagandizes and there’s so much Russia. There are eleven time zones, who’s to know, who’s to say what else is happening there? The centrality versus the periphery is an incredible combination.

Right, it’s very incredible. And I think a lot of people don’t know, like for example, there’s a group of people by the Mongolian steppes, the Buryat people, they look more Eastern Asian than they look like typical Russians as portrayed in Western media, but their identity is still Russian. However, in the U.S., people may completely mistake them for a different ethnic group and miscategorize them because everyone thinks of a very specific type of person as “Russian.”

Yes, for sure. You know, it’s funny, recently I went to Ithaca, New York, and I was driving around in a Greyhound bus, just looking out the window, I was thinking to myself, “America is too large.” There’s just no reason why Ithaca, New York should be in the same country as Los Angeles, California. I get why and the development of our history in why that’s the case, but today, practically, there’s no reason. That perhaps is doubly true for Russia. There’s no reason why the Yakut or the people in the steppes of Mongolia are the same people as the people in St. Petersburg. Maybe that’s an extreme view, but I don’t know why Ithaca is in the same country as Los Angeles.

Courtesy of Dav Yendler

I mean, yeah, if we’re talking “extreme” views, I would take that and say why do countries even exist in the first place?

Yes, which I didn’t really experience that opinion until I did these interviews! So many of my interview subjects wanted the destruction of borders — no more passports or visas. They wanted free travel between states. Maybe that’s speaking to an American ignorance, willful or not, but I’d never heard that before, that desire. It was really interesting to hear that from my Russian interview subjects.

That is very fascinating. I mean, as an aside, it’s interesting to note that Lenin wanted the entire world to eventually converge under global communism, and for there to not be different nations. I don’t think that that is blatantly what was drilled into the Russian people, but maybe this notion of being communal, or sharing the world, as opposed to ours versus yours, is prevalent.

Right, exactly, and that’s a very communist perspective to have in 2019, 2020.

Thank you for indulging all of my historical asides! To bring it back to your work, what has been your biggest personal accomplishment thus far as an illustrator and designer?

It’s a hard one to answer. The first thing that comes to mind is a clickbook I did on body image, which I struggle with all the time. It’s called “My Bod”, and essentially I sat down and figured out all of the ways that I drive myself insane with mirrors and photographs and reflections and I created a bit of an artistic process to help me cope with my own image. The clickbook walks you through my emotional experience, my epiphany, and my process. I posted it to Facebook, and then Upworthy reblogged it, and Buzzfeed got a hold of me to do an animated version featuring my voice, words, illustrations. It felt really good to walk into that studio and create the work for a larger audience, and then it went off to the Buzzfeed and YouTube distribution universe, where it got a bunch of clicks. That was really nice to see, because we don’t see a lot of men talking about their body image, even though the issue affects everyone.

Courtesy of Dav Yendler

Right, and that’s something that is so relevant. I’ve had some men share their issues with body image, which has made me wonder how frequently that happens because sometimes men don’t feel comfortable talking to each other or in general about these things. Not to necessarily focus on gender binaries or divisions, but I think it’s very much something that is important or needed for men and male-identifying people. To know that you can be a man and also feel all of these things, because the media may not necessarily portray that perspective.

Yes — and to note, that clickbook was my first brush with virality!

That’s rad! Do you have any exciting projects coming up that people can look out for?

I’m beginning to populate my Instagram account with smaller clickbooks, and have done a few recently to capture what’s going on with the phenomenon of COVID-19 and quarantine. “Other Russia” was uploaded as this massive, five-part megalith, and I’m doing more shorter things now — quick, fast uploads. I’m also playing around with a piece on guns in America, and specifically boyhood and guns, and I’m experimenting with a piece on posterity, children, babies, parents, and that whole thing.

The way that you approach these topics, and how you conceptualize them, reminds me of Eric Schlosser’s works. He’s a journalist and author who utilizes a completely different medium, he wrote Fast Food Nation (2001) and then several other works, including one on nuclear weapons. Your work is reminiscent because it presents topics through this fusion of creative innovation and journalism made palatable for a wide audience. However, I think your clickbooks can have even further reach because of your informed, but not inaccessible, perspective.

That, to me, goes back to clickbooks, which are all about accessibility and interactivity. People keep asking me over and over again when I’m going to make a comic book and when I’m going to make a graphic novel, and I am interested in those forms, but not a lot of people are buying books or keeping them on their shelves. However, they are looking at their phone, and if I can get my message to you, I’m going to get it to you through the way that is the most efficient and accessible.

Courtesy of Dav Yendler

Thank you so much to Dav for the incredibly enriching and thought-provoking conversation about his work and experience in creating “Other Russia.” Be sure to check out all of his work on his website, and follow his Instagram for more of his short-form clickbooks.